|

| Why do a marine debris survey at Miyako Island and the Pacific Northwest? |

|

|

| |

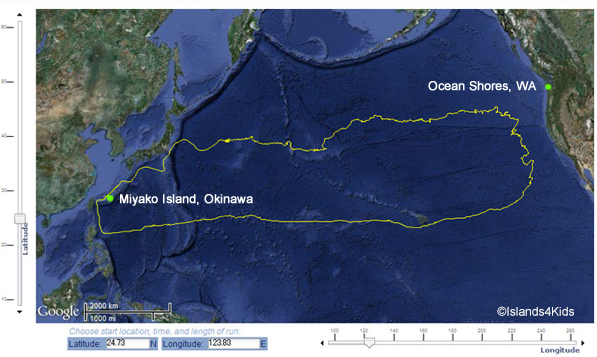

Miyako Island is at the starting point for many drifting trash. Debris from Asian nations pass by Miyako Island before their long trip across the Pacific Ocean.

The "Exit Survey of Asian Marine Debris" was done in Miyako Island to research the path taken by Asian debris. While some trash end up in the shores of Miyako Island, many still get carried on the Kuroshio (Black Current) and travel across the Pacific Ocean to the west coast of the U.S. and Canada.

To see if marine debris really travels that far, we have been doing "Survey of Arrival Situation" in Ocean Shores, WA. Through our arrival situation surveys, we have found Asian marine debris produced in China, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Indonesia and Malaysia. This gives us reason to believe that those trash came directly through the Kuroshio (Black Current). However, it is still not certain where the debris actually started its journey. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

The most of the Taiwan Warm Current extention marges to Black Current at the north of Miyako Island, so as the marine debris. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

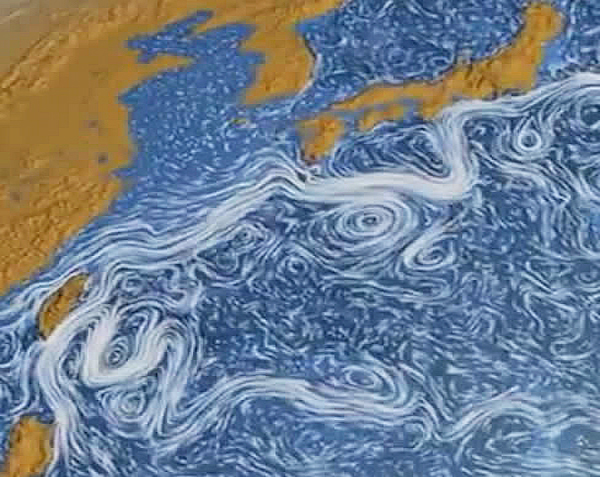

Photo courtesy: Scientific Visualization Studio, NASA |

| |

This image is a visualization of ocean current movements by NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio using data from June 2005 to December 2007.

This image shows two large currents merging north of Taiwan and branch currents (split flows) starting to circle around Miyako Island and other neighboring islands of Okinawa. As a result, many Southeast Asian marine debris wash ashore Miyako Island. |

| |

|

|

How debris travels in the Pacific Ocean |

| |

|

| |

This is a typical course of Black (Kuroshio) Current. Black Current is a fast moving ocean current on the North Pacific Ocean circling clockwise.

Marine debris that leaves Southeast Asia takes about two years to reach the pacific coast of the United States, and another two years to return to Asia. So, a roundtrip movement from Southeast Asian takes roughly four years. |

| |

|

What is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch? |

| |

When you think of a "Great Pacific Garbage Patch", you might think of enormous regions or patches of marine debris. Might we be able to see long stretches of debris piling up like a landfill or even forming small islands of debris? Despite its name, a lot of the marine debris of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch are made of small fragments of plastics or styrofoam. They are not just floating on the ocean surface either. Marine debris can be found at a depths of close to 30 meters deep. For this reason, it is also possible to sail through the garbage patch.

It is difficult to obtain accurate information on the size of the garbage patch.

The ocean is continuously moving, meaning the debris will also be moved and mixed constantly by forces of the wind and currents. While we might not know how vast the spread of the garbage patches may be, what we should realize is that marine debris is a serious issue.2

What are the “garbage patches”?

“Garbage patches” are areas of marine debris concentration. As mentioned above, these patches of marine debris do not form islands or other large formations that can be seen by satellite or aerial photographs.

Though the specific locations cannot be specifically identified, there are two approximate areas of garbage patches. The “eastern garbage patch” is located approximately within the North Pacific Subtropical High between Hawaii and California. The “western garbage patch” may be located near the Kuroshio current off the coast of Japan.3 |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

How the actual Tsunami debris of 2011 Traveled? |

| |

|

|

How the actual Tsunami debris of 2011 Traveled? |

| |

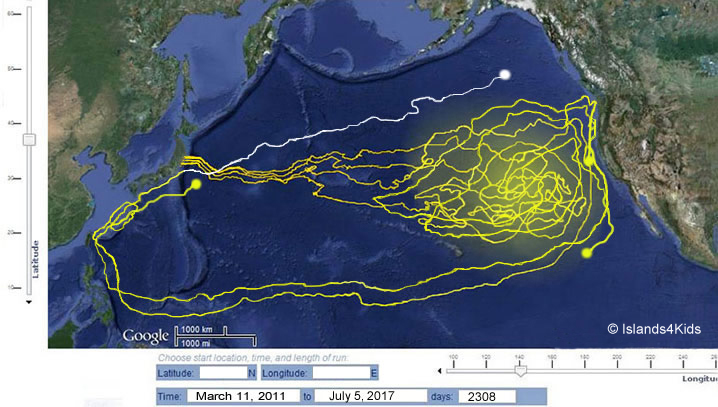

Until July 2017, NOOA used a satellite observation system called OSCAR to publish monthly tidal currents in the Pacific Ocean as part of its oceanographic observations. Using this data, we could track the ocean currents' monthly from each of our checking points.

We animated this data in our own developed simulated gif program and continued to track the course for six years, four months, and 2,308 days. This is the course in the photo above.

To begin tracking the tsunami-related marine debris that washed up on the Pacific Ocean in the aftermath of the March 2011 Tohoku earthquake and followed the tsunami, we focused on the three cities hardest hit by the tsunami the debris flow from the Fukushima Daiichi (#1) Nuclear Power Plant. We were particularly interested in when and how this marine debris would arrive at the Pacific Northwest's costs. |

| |

| |

|

Why can't we simply clean the ocean? |

| 1. |

Since debris flows and moves around in the ocean, it will take lots of time to locate specific areas of debris. A lot of money will be needed for this! |

| 2. |

Scoping up all the debris may sound simple, but it's not! Surprisingly, there are many sea creatures such as plankton, jellyfish, as well as fish and coral eggs that live among the floating debris. By scooping up the debris, that will mean that many sea creatures will be taken as well. This will harm the ecosystem. |

| |

|

| |

During our July 2014 Marine Debris Arrival Survey, we found a 2 inch lightbulb that held some marine life. While much of the metallic components of the bulb has degraded, the filament remains. We might see this lightbulb as marine debris, but for these marine critters, it is already their home. |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

See the poster |

| |

|

| |

|